|

| Ben stands next to a cannon at Spotsylvania. |

When we went to Quantico, VA to see Christian's graduation from Marine Corps Officer Candidates School and his commissioning as a second lieutenant in March 2015, Ben and I wanted to see some Civil War sites. In Virginia, it is almost impossible to swing a dead cat without hitting a marker about the US Civil War. We stayed at Fredericksburg the first night in the DC area and were in the middle of the overlapping battlefields of Fredericksburg (December 1862), Chancellorsville (May 1863), Wilderness (May 1864) and Spotsylvania Courthouse (May 1864).

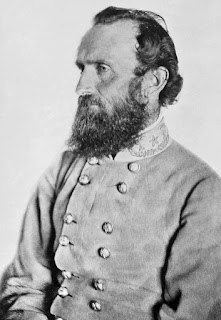

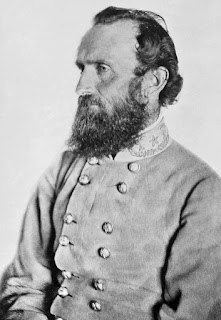

A common assumption in American thinking is that one person does not an organization make. In the extreme, that is true, but it may take one person to serve as the glue that holds an organization together. Strange though he was, Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson was a man that understood orders issued in polite Southern speech. He was the man that brought Robert E. Lee's battle plan to fruition, and it is often argued that the friendly-fire death of General Jackson was the beginning of the end for the Army of Northern Virginia and the Confederate States of America. Because of his position in Civil War history, Ben and I decided that we'd like to see the house in which Gen. Jackson died.

Thomas Jackson

Jackson was a "self-made" man, working his way up in the world despite a difficult childhood. Jackson's parents were Jonathan Jackson, an attorney and Julia Jackson. The family plunged into poverty when typhoid struck the family when Thomas was two. The death of Jackson's father and sister left Julia a widow at 28 with four children to care for, including a newborn. Julia refused family charity, sold off their possessions, moved into a small cabin, and took in laundry and taught school to earn a living. Thomas' mother married Blake Woodson in 1830, but he did not like her children. As the family continued to struggle financially and Julia's health declined during pregnancy, the family was split up among the relatives of Jonathan Jackson and Julia. This arrangement became permanent with the death of Julia Woodson in 1831.

|

| Thomas Jackson in US Army uniform |

Sent first to Jackson's Mill and his Uncle Cummins Jackson, after four years Thomas was sent to his Aunt Polly's. After enduring verbal abuse from Aunt Polly's husband, Isaac Brake, Thomas ran away and found his way back to the grist mill. He developed a hard work ethic on the farm, attended classes when possible and read when he could. Eventually he earned his keep by teaching school, before gaining admission to the US Military Academy at West Point.

Starting out last in his class. largely due to his lack of formal preparation for the strenuous curriculum, he worked his way up to 17th in a class of 59 in 1846. Commissioned a second lieutenant in the US Army, his aggressive use of artillery during the Mexican-American war led first to a promotion to full lieutenant and a brevet commission as major.

Jackson returned to teaching school as a Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy and instructor of artillery at Virginia Military Institute at Lexington, VA in 1851. A poor lecturer, he memorized his lectures. showed an inability to deviate from that narrative on the fly and considered students who asked the same question twice to be insubordinate. Although he lacked the respect of students at that time, and was poor in the lecture room, he was a military visionary. The artillery curriculum that he developed at VMI before the Civil War stressed discipline, mobility, efficient use of artillery supported by an infantry assault, and discovering enemy strength and intention without giving away one's own plans. These ideas are still taught to military students, as they are essential regardless of weapons development.

|

| Lt. Gen. Thos. Jackson 24 Apr 1863 |

Application of these ideas to the Confederate cause in the service of the Army of Northern Virginia during the Civil War earned "Stonewall" Jackson the respect of soldiers that he lacked from his students. His performance at battlefields such as Manassas (First and Second), Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville made Jackson a must study commander for all American military officers since. His disciplined approach in battle failed him seldom and his campaigns forced much larger Union armies to be held out to defend Washington, D.C. Over 150 years have passed since his death and he still ranks as one of the all-time great American military leaders.

The Death of "Stonewall"

During the Battle of Chancellorsville, Lee decided to divide his forces and try to flank the Army of the Potomac and its new commander, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. Jackson's forces entered The Wilderness on 2 May 1863 in an attempt to find the Union right and rear. Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry was successful in probing the Union lines, and Jackson marched his II Corps through the dense growth, catching the Union Army unawares. Charging from just a few hundred feet from Union forces, Jackson rolled up the Union right. Only nightfall brought an end to infantry action. Artillery barrages would continue through the night to the next day.

|

| Fairfield plantation office |

As Jackson returned to camp with his staff, pickets from the 18th North Carolina Infantry mistook them for Union forces and fired on them before they could answer the sentry's challenge. Even after Jackson's staff identified themselves, the North Carolinians, suspecting a Union trick fired a second volley. In the end, Jackson suffered three wounds: two in the left arm and one in the right hand. At least one other staff member was killed and another wounded. The worst of Jackson's wounds broke the humerus (upper arm bone) and severed the brachial artery of the left arm. Jackson was helped from his horse, nearly fainting in the process, and a tourniquet was applied to the general's left arm by his aide-de-camp.

|

| Site of Fairfield directly across from the office |

In the end, delayed medical care probably doomed Jackson. At first, his men tried to walk Jackson out, but Union artillery fire slowed their progress. He was dropped from his stretcher, and progress to a field hospital was very slow, even after reaching an ambulance. At the Chancellor House, Dr. Hunter McGuire, chief surgeon of Jackson's corps, took charge of the general's care. McGuire observed that Jackson's uniform was saturated with blood because the upper wound was still bleeding and so the doctor readjusted the tourniquet. Without this care, the general would likely have been dead within 10 minutes. Given the extent of the injuries and owing to the loss of a lot of blood , McGuire found little to do but amputate Jackson's left arm.

|

| General Jackson's deathbed |

After surgery, Jackson appeared to be in good spirits, engaging in conversation and sending for his wife to be with him as he convalesced. Lee, fearing that the field hospital would be overrun by Union forces, ordered Jackson's evacuation to Guinea Station on May 4th to the south and east of the battlefield. This was a major staging area for Lee's forces and Hooker's forces had torn up the track to the south, cutting Lee's supply lines. This would be an ideal point for departure to Richmond, once repairs could be made to the railroad. Pioneers were deployed to remove obstructions and smoothen the road. The journey over the rough roads was difficult, taking about 12 hours to move the 27 miles from the field hospital. "Fairfield", owned by Thomas Chandler was offered for Jackson's recuperation. The general chose the plantation office for his quarters, not wanting to unhouse the family. This was for the best as Dr. McGuire discovered that a patient already housed in Fairfield had a contagious disease.

|

| Dr. McGuire's couch in the sickroom |

At first, it seemed that the general would recover. McGuire limited visitors and Jackson slept well through the first night. Rev. Beverley Tucker Lacy held a prayer service at Jackson's bedside the following day, which comforted Stonewall greatly. Rev. Lacy retrieved Jackson's left arm and buried it in the family cemetery at Lacy's brother's house, Ellwood. McGuire went to sleep in an adjacent room that night, thinking the general was recovering.

At about 1 AM, Jackson was feeling nauseated and asked his servant to put wet cloths on his side, which had been in pain since shortly after the amputation. When Jackson finally allowed McGuire to be awakened, the doctor found his patient exhibiting classic symptoms of pneumonia. Mrs. Jackson arrived with their baby daughter and seemed to grasp the gravity of the situation quickly. Jackson would sink into delirium, then recover and talk to his wife and hold his daughter, then the cycle would start again. On 10 May, he was informed by his wife that the doctors thought that he would die that day. Consulting with Dr. McGuire, Jackson said "Very good. Very good. It is all right." The reverent Jackson thought it proper to die on a Sunday.

|

| The view from the upstairs |

Jackson's condition deteriorated through the day, and he sunk into a final delirium. After preparing for one last battle in his dreams, he said "Let us pass over the river and rest under the shade of the trees." He died at about 3:15 PM.

His death was a hard blow to the Confederacy, and Lee would never be able to find another subordinate that understood his orders and provide balance to the more defensive-minded Longstreet. Jackson laid in state in Richmond, VA, where thousands filed past his coffin in the capitol rotunda. His remains were then transported by train to Lexington, VA where he had taught school at VMI. He was buried in what is now Stonewall Jackson Memorial Cemetery.

Soon after his death and the end of the Civil War, the Chandler farm, Jackson's grave, the burial site of his arm and the site of his wounding were marked and visited by a stream of people. The Chandler farm was visited by none other than Union General Ulysses S. Grant during the 1864 campaign. In 1911, the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad, owners of the property, decided to dismantle all but the building where Gen. Jackson died, as the plantation had fallen into disrepair. It was the railroad that gave the site the name "Stonewall Jackson Shrine". In 1937, the property was sold to the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, which is currently part of the National Parks system. The care of the site is evident. About 40% of the building material in the shrine is original, many of the furnishings, including the deathbed and a bed cover, are original. The marker at the site is one of a dozen similar markers placed by James Power Smith (Jackson's aide-de-camp) in 1903 commemorating Jackson, Lee and John Pelham.

|

| Nadienne and the kids viewing the markers. |

Disease and war

|

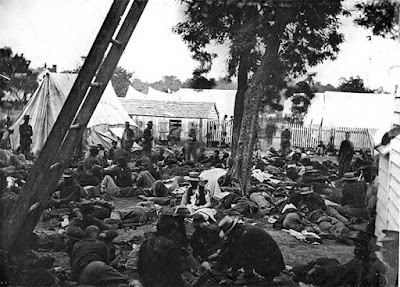

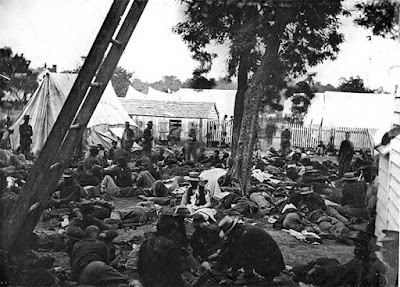

| Civil War field hospital |

The experience of Stonewall Jackson is not uncommon among soldiers in war. The ratio of soldier's deaths due to disease compared to battle wounds was 7:1 in the Mexican-American War; 2:1 in the Civil War and 5:1 in the Spanish-American War. These deaths were caused by a variety of illnesses. Some of them, such as typhoid fever and dysentery were linked to poor sanitary conditions. Others were due to parasitic infections, such as worms and malaria. Diseases spread by respiratory droplets were also common: smallpox, measles and pneumonia. Lack of sterilization procedures meant that many wounds became gangrenous or the patients contracted septicemia (blood poisoning). A weakened post-operative patient exposed to patients with pneumonia would very likely contract pneumonia themselves.

Studies and work by health care professionals such as Florence Nightingale in the Crimean War were instrumental in halting the spread of disease in camps. Many campaigns were lost in the end because of disease. Typhus defeated Napoleon in Russia to a greater extent than any army. Crusaders were turned out of Palestine more by dysentery than any other factor. The first army to suffer more deaths from battle wounds than disease were the Germans in the Franco-Prussian war of 1870.

Getting There

Your best bet is to check one of the websites and follow detour signs at present. The most direct way to the shrine is blocked by a washed out bridge at present.

Waypoint: Latitude: 38.147864 N; Longitude: 77.4423529 W

Street Address: 12023 Stonewall Jackson Road, Woodford, VA 22580

Hours for the Stonewall Jackson Shrine change seasonally, so it is best to consult the website for updates.

Further Reading

The Curious Fate of Stonewall Jackson's Arm

The Death of Jackson

Virtual Tour Stonewall Jackson Shrine

Stonewall Jackson Shrine Web Page

Disease and Death in the Civil War

|

| Office building from the parking lot. |