|

| Chimney Rock and Scott's Bluff on horizon |

|

| Historical marker about a mile from gravesite |

Amanda's Story

|

| 1850 Census lines (cropped with titles from top of sheet) for Maupin-Lamme families |

|

| Amanda's broken original marker, and 1912 marker |

Jack Lamme and Thomas Maupin found a grove

|

| 1912 marker |

Jack would catch back up to the family wagons and in October 1850, they pulled into Marysville, California. In the 1860 US Census, the girls were living with the Maupins and in the 1870 Census Alcis' last name is listed as Maupin. Jack mourned for Amanda for a long time, going back to Boone County in 1858 where he married Semiramis Echols on 02 April. They had two children, Joseph born 1861 and Ida, born about 1860. Alcis married Howard Cunningham and died in San Francisco 03 January 1918. Laura Lamme was married on 29 March 1871 in Buchanan County, Missouri to William Burton White. William died on 02 January 1878 and Laura never remarried. She died 05 May 1923 in Alameda, California.

|

| Amanda and Jack's marriage record from Boone Co., MO |

A new marker

Nebraska Territory was opened up to permanent settlement in the 1850s and free-ranging cattle in the area trampled and broke the marble headstone bought by Jack. Locals remembered the old marker and gathered what they could find and tried to piece together what the old marker said. What they came up with was:

AMANDA

Consort of M.J. Lamin

of Devonshire, Eng.

Born February 22, 1822.

Died June 23, 1850, of Cholera.

Amanda was born in Missouri and her parents were born in Kentucky. It seems entirely likely that the well-intentioned citizens of Bridgeport found the remains of two markers and tried to cobble them together into one cohesive marker. Allowing for the damaged name, everything jives, except for the birthplace. Another pioneer from Devonshire, England must have been buried in the same grove of trees. It is prescient since I know that her husband's family was originally from Devonshire, and it is likely that her family was as well.

Living in a time of cholera

|

| 1800s medical text illustration of effects of cholera (right) on a patient |

Cholera is a bacterial infection that induces a massive

watery diarrhea, transmitted by contaminated drinking water or foodstuffs

contaminated with fouled water. The

diarrhea is copious, almost beyond understanding pumping an amazing 2 liters of

water out of the body each hour. Without

fluid replacement, the blood increases in viscosity, making it increasingly

difficult for the heart to push blood through the circulatory system, leading

to shock and collapse of vital organs. The eyes become sunken, the skin wrinkled, cramps result from loss of minerals and fever spikes. Death often takes place within hours of symptom onset.

|

| Vibrio cholerae bacterium |

The cause is a comma-shaped bacteria called Vibrio cholerae. When the bacteria is exposed to stomach acid, it signals the bacterium to start making a toxin that causes cells to pump chloride ion into the intestine, pulling water along with it. The cells lining the intestine are shed into the water passing through resulting in rice-water stools. It costs less than $1 in materials to support a patient with cholera. Water with a bit of sugar and salt to replace lost fluids is all that is required. The patient will pass so much fluid that it will flush the bacteria out of the gut (self-limiting).

|

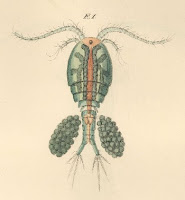

| Cyclops copepod |

The bacteria can persist in the environment for a long time, because they can live inside copepods (small aquatic organisms) in slow moving streams. People drinking this water without filtration or treatment can swallow the copepods and release the bacteria. If you hold up a jar of pond water to the light, the little white specks that flit around are probably copepods. Over 250,000 cases of cholera still occur world-wide each year, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa.

"In wine there is wisdom, in beer there is freedom, in water there is bacteria" - Benjamin Franklin

Second Asiatic Cholera Pandemic

|

| Route of spread of cholera from India to Americas in 2nd pandemic |

The second pandemic of cholera originated in India in about

1829 and spread through the United States in 1832. The second major epidemic in the United States started in about 1849, corresponding with a major gold rush to

California and the Mormon migration to Utah. This epidemic of cholera was a major cause of death of westward emigrants from 1849-1851.

A collapse of the United States economy in 1837 drove people from the east to the west with the prospect of a new start and cheap land. Using a trail first pioneered by fur traders to the Oregon country, a trickle of emigrants began using the trail from Independence, Missouri to Oregon in 1836. Soon, each spring found the population of Independence swelling several-fold, as the emigrants began staging for the trip west, waiting for the grass on the prairie to green enough for the grass to support grazing animals. Once the conditions were right to move on, wagons waited in line for days to travel the ferry across the river.

A collapse of the United States economy in 1837 drove people from the east to the west with the prospect of a new start and cheap land. Using a trail first pioneered by fur traders to the Oregon country, a trickle of emigrants began using the trail from Independence, Missouri to Oregon in 1836. Soon, each spring found the population of Independence swelling several-fold, as the emigrants began staging for the trip west, waiting for the grass on the prairie to green enough for the grass to support grazing animals. Once the conditions were right to move on, wagons waited in line for days to travel the ferry across the river.

|

| Mosquito Creek by trail campground near Troy, KS |

|

| Native stone markers in Courter-Richey Cemetery on St. Joe Road |

Cholera and overcrowding in Independence pushed emigrants to

points further north at Saint Joseph, Missouri and old Fort Kearny (now

Nebraska City), Nebraska. Saint Joseph

was incorporated in 1842, becoming a boomtown in 1849 as people flocked to

California in search of gold. Cholera

outbreaks in Independence pushed a majority of the ‘49ers to the Saint Joseph

trailheads. No cholera outbreaks

occurred in Saint Joseph, but many emigrants began to die from cholera within a

day after hitting the trail. Several

small cemeteries in the Northeast Kansas countryside were started as burial

grounds for cholera victims. Many graves marked with native stones are thought to contain the bodies of cholera

victims.

|

| Mosquito Creek campground area near Troy, Kansas |

“Camped last night on the bank of the Nemaha river,

and this morning were called upon to bury a man who had died of cholera during

the night. There have been many cases of this disease, or something very much

like it; whatever it may be it has killed many persons on this road already.

Yesterday we met two persons out of a company of five who left St. Joe the day

before we did; two had died, one left on the road, sick, and the two we met

were returning. There are many camps on the banks of this river; many are sick,

some dead and great numbers discouraged. I think a great many returned from

this point; indeed, things look a little discouraging and those who are not

determined may waver in their resolution to proceed. This afternoon we passed

the graves of a man and woman; the former was marked for seventy-four years.”

|

| Native stone likely marking a cholera victim's grave in Courter-Richey Cemetery |

“Just

after we started this morning we passed four men diging a grave. They were packers The man had died was taken sick yesterday

noon and died last night. They called it

cholera morbus The corpse lay on the

ground a few feet from where they were diging

The grave it was a sad sight…. On the bank of the stream waiting to

cross, stood a dray with five men harnessed to it bound for California, They

must be some of the perservering kind I think Wanting to go to California more

than I do…We passed three more graves this afternoon.”

These were hardly unique experiences. Some estimates put the 1849 death toll at between 1500-2000 and the 1850 cholera death count at over 1000. Ezra Meeker suggested that the count was closer to 5000 in 1850 noting that the dead were often buried in rows of 15 or more.

These were hardly unique experiences. Some estimates put the 1849 death toll at between 1500-2000 and the 1850 cholera death count at over 1000. Ezra Meeker suggested that the count was closer to 5000 in 1850 noting that the dead were often buried in rows of 15 or more.

Six Degrees....

|

| George IV Boone's will mentioning Dinah |

Getting There

Gravesite Waypoint: Latitude 41.605433 N; Longitude 102.9802684 W (private land)

Historical Marker Waypoint: Latitude 41.612911 N; Longitude 103.003697 W

Further Reading

Amanda Lamme

Thank you for shedding so much more information on this lonely grave. All I knew before was from this Nebraska historical marker to the west, and it didn't have much. Great research.

ReplyDelete